Two bonobo chimpanzees in Iowa are changing how scientists think about the nature of human language.

Kanzi and Panbanisha understand thousands of words. They use sentences, talk on the phone, and they like to gossip. In short, they use language in many of the same ways humans do.

That's not supposed to be possible.

Since the 1950s, linguists including Noam Chomsky have argued that language is unique to humans and requires an innate understanding of grammar.

A Classroom Accident

But the achievements of Kanzi and Panbanisha suggest otherwise, says Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, head scientist at the Great Ape Trust near Des Moines. She says apes can acquire a lot of language if they learn it the same way human babies do.

Savage-Rumbaugh says she discovered that by accident in the 1980s, shortly after Kanzi was born.

At the time, she was at Georgia State University trying to teach words and symbols to Kanzi's adopted mother, Matata. Kanzi was in the classroom, too, but Savage-Rumbaugh wasn't trying to teach him anything.

"Kanzi would just be around," she says. "He would often be on my head, or jumping down from the top of the keyboard into my lap. If we asked Matata to sort objects, [Kanzi] would jump in the middle of them and mess them all up. So he was just a normal kid."

Savage-Rumbaugh suspected that Kanzi recognized a few words. But she says it wasn't clear how much Kanzi really knew until he lost his mother.

Matata was taken away for breeding when Kanzi was 2 years old. At first, he thought his mother was hiding. When he couldn't find her, little Kanzi was bereft.

An Urge to Talk

So he turned to his best friend, Savage-Rumbaugh. Kanzi desperately wanted her help, and he began to ask for it by pointing to symbols on Matata's keyboard.

Savage-Rumbaugh says Kanzi used the keyboard more than 300 times on the first day he was separated from Matata. He asked her for food. He asked for affection. He asked for help finding his mom.

At the time, Savage-Rumbaugh was too worried about Kanzi to fully appreciate what he was doing.

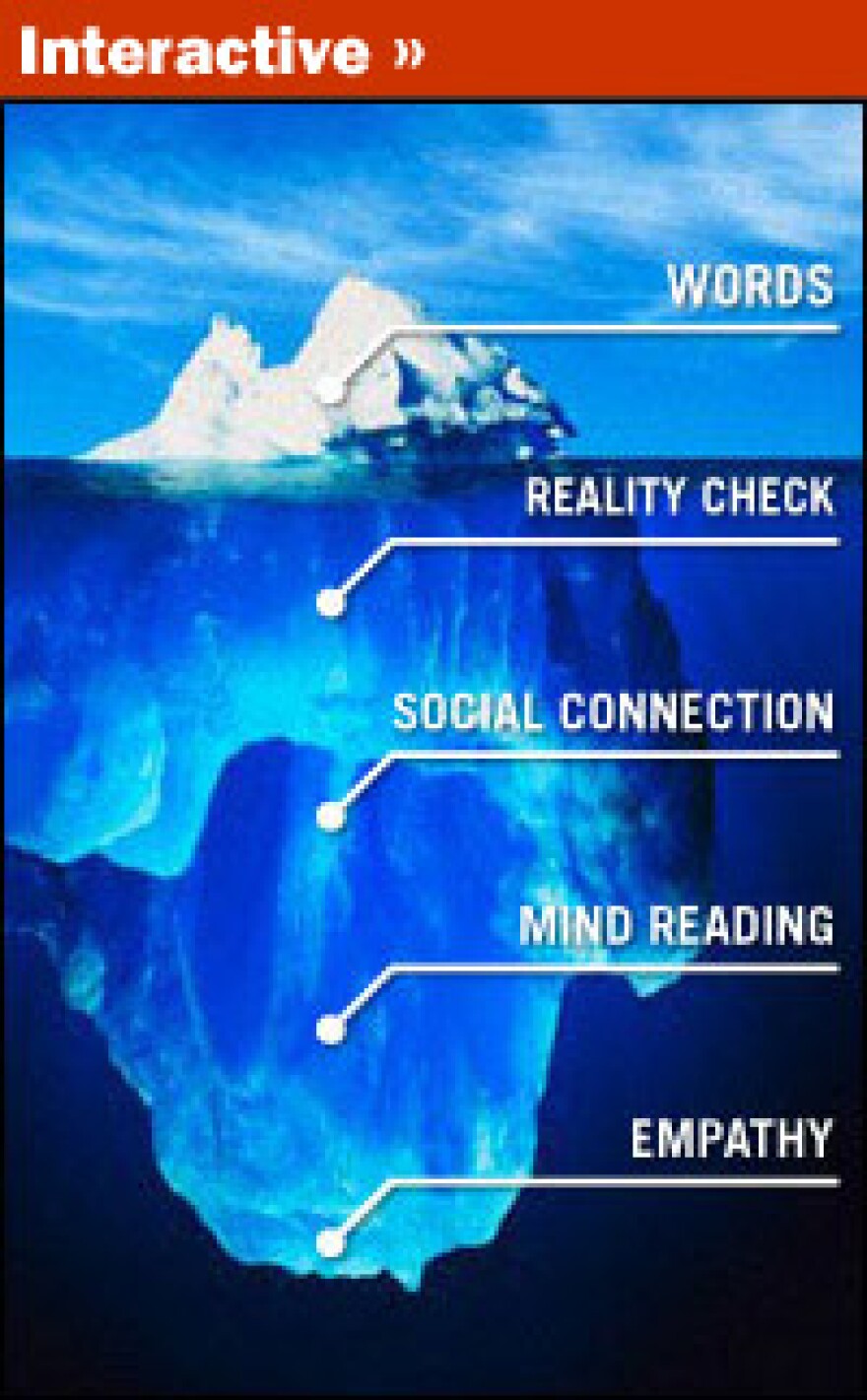

But later, she had an epiphany: Whatever language was, it was more than words and sentences. It must have deeper roots in social connections and a shared understanding of the world.

A New Way of Teaching Language

Savage-Rumbaugh made a decision; She would stop trying to teach words and sentences to apes. She would give Kanzi a reason to talk, and something to talk about.

"What I had to do is come up with an environment," she says, "a world that would foster the acquisition of these lexical symbols in Kanzi and a greater understanding of spoken human language."

Savage-Rumbaugh created a world where Kanzi would learn the way human babies do. He and his human friends would eat together and play together. And because bonobos love to travel, Savage-Rumbaugh and Kanzi would hike around their 50-acre home.

"Whenever we talked about a travel destination, we had Kanzi's immediate attention," Savage-Rumbaugh remembers. "And if we showed him a photo, he wanted to hold it, he wanted to ride on our shoulders and hold the photo and look at it all the way to the place."

Before long, Kanzi was doing many of the things humans do with language. He was talking about places and objects that weren't in sight. He was referring to the past and the future. And he was understanding new sentences made up of familiar words.

The Tests

Kanzi and Savage-Rumbaugh often sat beside a somewhat polluted river. Every now and then, a Coke can would float by. Savage-Rumbaugh explained to him that people had thrown the cans in the river. At first, she wasn't sure Kanzi understood.

Then, one day she said, "Kanzi, could you throw your Coke into the river?" Kanzi immediately reached into their backpack, took out the Coke and threw it in the river.

Savage-Rumbaugh concluded that Kanzi must have understood what the words meant when spoken in that order.

But linguists were skeptical. They said the sentence, "Throw the river in the Coke," might have produced the same response. They also said Kanzi might have been reacting to her body language, not her words.

Savage-Rumbaugh was determined to prove that Kanzi really did understand sentences. So she asked him to take a series of scientific language tests.

In one of the tests, which was videotaped, Savage-Rumbaugh wears a welder's mask so Kanzi can't see her face, and she makes no gestures. She asks Kanzi to perform dozens of unlikely tasks, like putting pine needles in the refrigerator. He understands nearly every request.

In these tests, Kanzi was doing what linguists said no ape could do. And later, Kanzi's little sister, Panbanisha, would perform even better in similar tests.

Creative Language

But linguists still weren't satisfied. They pointed out that humans invent metaphors and figures of speech when literal meanings aren't enough.

Savage-Rumbaugh says the bonobos pass this test, as well. For example, Panbanisha once used the symbol for "monster" when referring to a visitor who misbehaved.

Bill Fields, a researcher at the Great Ape Trust and a close friend of Kanzi, recalls another time when Kanzi used language creatively.

Fields says it was during a visit by a Swedish scientist named Par Segerdahl. Kanzi knew that Segerdahl was bringing bread. But Kanzi's keyboard had no symbol for Segerdahl the scientist. So he got the attention of Savage-Rumbaugh's sister, Liz, and began pointing to the symbols for "bread" and "pear," the fruit.

"Liz got it immediately," Fields says. "She says, 'What do you mean Kanzi? Are you talking about Par or pears to eat?' And he pointed over to Par."

Fields says that because Kanzi was raised among humans, he has a powerful desire to communicate with the humans in his world.

"He wants to share," Fields says. "He wants to do things with people. He wants people to know how smart he is. He wants people to know what he can do. And occasionally he'd like to be able to tell people to do things for him that he can't do for himself, like go down to the Dairy Queen and get him an ice cream with chocolate on it."

Fields says they used to do that before Kanzi went on a diet.

Kanzi's Theory of Mind

Kanzi also has developed a skill closely associated with human language, Fields says. It's called theory of mind — and a growing number of researchers believe it is at least as important as grammar.

Theory of mind means recognizing that other people have their own beliefs and desires. It also allows someone to imagine the world from another person's point of view.

Scientists disagree about whether apes have this ability. But Fields has no doubt.

"I'm missing this finger," Fields says, holding up one of his hands. "One time when Kanzi was grooming my hand, when he got to where the missing finger is, he pretended like it was there. And then he used the keyboard, he uttered, 'Hurt?,' as though to say, 'Does it still hurt?' "

Kanzi's sentence contained just one word: hurt. But Fields says the sentence reveals something about the very nature of language: Words depend on the social context that produced them.

At the Great Ape Trust, the bonobos have found ways to extend their social ties with humans — like talking on the phone.

Straddling Two Worlds

Savage-Rumbaugh says that talking on the phone helps Kanzi and Panbanisha cope with their odd status as creatures who socialize with humans, but are not human themselves. (Kanzi can make sounds that mean yes or no, and uses a lexigram keyboard for more complicated phone conversations.)

"They are aware of that, and sometimes it's a sadness because they realize they can't go everywhere we can go and can't do everything that we can do," she says.

The apes can't go back to the wild either. Bonobos in the Congo have been all but wiped out by hunters. And Kanzi and Panbanisha lived with humans for too long to be able to live on their own in the wild.

The apes are straddling two worlds, and Savage-Rumbaugh says they seem to know it. She says both apes like to watch movies that blur the boundaries between humans and apes.

"Kanzi's favorite movies when he was very young were Ice Man and Planet of the Apes," Savage-Rumbaugh says. "I guess his favorite movie of all time is Quest for Fire."

Produced by NPR's Anna Vigran

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.