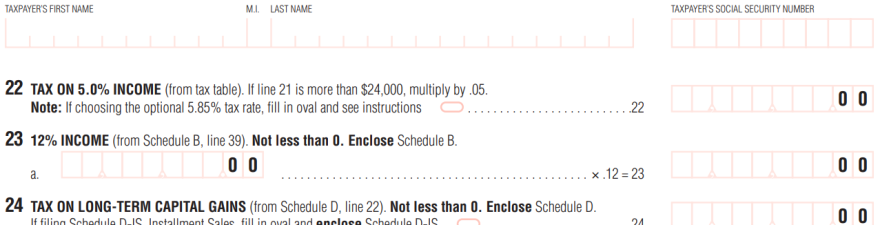

Question 1 is a proposed constitutional amendment on Massachusetts ballots that would establish an additional 4% state income tax on annual taxable income over $1 million.

Revenue from this tax would be dedicated for public education and transportation, subject to the Legislature's appropriation of that money.

For a short debate on the question, we were joined by a supporter and an opponent. Andrew Farnitano is a spokesperson for Fair Share Massachusetts, a group urging a "yes" vote. Dan Cence is a spokesperson for the Coalition to Stop the Tax Hike Amendment, which wants Massachusetts residents to vote "no."

Kari Njiiri, NEPM: Dan, you claim Question 1 would nearly double the state income tax rate on tens of thousands of small business owners and family farmers, homeowners and retirees. But we should be clear: A taxpayer's first million in income is taxed at the lower 5% rate. It's only income above that that is subject to the 9% rate. Why shouldn't people with means pay a larger share to support crucial services, like they do for federal taxes?

Dan Cence: Thank you. I appreciate the question. Uber-wealthy people and people with great means most likely will not be tremendously affected by this, Kari. What we're here today to talk about is the middle class of Massachusetts who perhaps would only be affected by this tax one time in their life — when they sell a home, sell a small business, sell a farm, or have some event in their life whereby they would enter into this tax bracket one time and then prepare to retire or pass that money down to their children. And we feel it's unfair for them to pay a significant increase — 80%, if you calculate it — that one time that they enter into this classification.

Andrew, you say the current tax rules allow multimillionaires to pay a smaller share in taxes than the rest of us, and so the rich should pay their fair share of taxes. But why won't wealthy people move to states like New Hampshire and Florida that don't tax regular income, and Massachusetts would lose all their tax dollars?

Andrew Farnitano: Kari, thank you. If the billionaires and multimillionaires were able to avoid this tax so easily, they wouldn't be spending millions and millions of dollars trying to fight it on the ballot. They are funding a multimillion-dollar campaign to convince voters to vote "no" with lies about how this would affect homes. There's been a ton of research on this issue. Less than 1% of homes in the state sell for enough of a gain to be affected by Question 1. Only seven homes in western Mass., all of western Mass., last year sold for enough to generate a capital gain of over $1 million.

So what Dan said about the middle class is just not true. Middle-class people will not be affected, whether they're retirees, home sellers or small business owners. This tax will only affect those at the very, very top, the top 1% of income earners. And they are fighting hard to convince voters to vote "no" because they know that they will pay more when we pass this in November.

Andrew, the argument is that this money will go towards public education and transportation, but there's no guarantee that the Legislature won't just use it to displace current funding. So shouldn't voters be suspicious of the promise of additional funding for these services?

Farnitano: Thanks. Let's be clear about what Question 1 does. So Question 1 raises this tax on income over $1 million and constitutionally dedicates the funding to education and transportation. It's not just a regular law or a regular ballot question. It will put that legal restriction in the text of the [state] Constitution that the money raised must be spent on education and transportation. That is stronger than any other possible thing we could do to ensure that more money goes to education and transportation. It's the strongest possible legal requirement.

We've got a coalition of more than 500 organizations across the state, teachers and health care workers and small business owners, who are going to stick around after Election Day to make sure that the money is additional money that reaches our local schools and our local roads and bridges. Attorney General Maura Healey has reaffirmed that she thinks the money will be additive on top of what's being spent today. And we wouldn't be fighting so hard to pass this if we didn't believe that the money will go to roads and schools and public transportation.

The need is so great. There are so many crumbling bridges across the state, more than 200 in western Mass. that are structurally deficient and in need of repair. Our public school students are seeing test scores that have dropped down to a level we haven't seen since the early '90s. We need more resources in our schools and our transportation system to build a better economy that works for everyone. And Question 1 will allow us to do that.

Dan, Massachusetts has had a big surplus in recent years and high tax revenues and billions in federal relief money part of that surplus. But there were many years when that was not the case, and the Baker administration has said it expects revenues to drop as this fiscal year continues. Why shouldn't the state set itself up for long-term stability to pay for necessary programs?

Cence: Well, Kari, the state should set itself up for long-term stability, but the funds generated from this tend to be more in capital gains and things that fluctuate much greater when the economy is going well. There's been studies that show that this could fluctuate anywhere from $900 million to $1.2 billion to $2 billion. And the bottom line is that it's not going to be a consistent revenue source. So it's not something that you can plan on.

And we do have a massive surplus. We have $8 billion in our stabilization fund, the largest in the history of the state. We have $10 billion in funds coming down from the federal government to help with our roads and bridges in the infrastructure bill. We're giving back $2.94 billion in overpaid taxes to the taxpayers of Massachusetts because of the economy and where it stands today.

And finally, these monies, as you've said before, aren't guaranteed to increase education or transportation funding. Members of the Legislature were asked by the Boston Globe recently and their response was, there is no guarantee that this will increase. So we don't know where it's going necessarily at the end of the day, we don't know how much it's going to be, and we don't need it right now.

Dan, a Tufts analysis found that as few as 0.6% of households will pay more because of this tax. Still, your campaign is focusing on small business owners when your top contributors are huge businesses, financial firms and CEOs — people who have a lot to lose if this passes. How does this reality match the talking points?

Cence: Well, the reality is we represent an organization of over 1,000 individuals and businesses that have signed up that represent over 25,000 companies in Massachusetts and hundreds of thousands of employees who've read the language, who understand where it is, and who stand together to say this will harm them, small businesses and large businesses alike.

The Boston Chamber of Commerce, the Cambridge Chamber of Commerce, the Mass. Retailers Association, the Western Massachusetts Economic Development Council, the Massachusetts Farm Bureau, Kari, all stand with us in opposition of Question 1.

Andrew, one main argument against this has to do with taxpayers whose income usually never approaches $1 million. But when they sell their business or property — looking to retirement, perhaps — they'll get hit with a huge tax bill. Why should those taxpayers be treated the same as people making millions every year?

Farnitano: If someone makes less than $1 million most of the time and one year they make a little bit over $1 million, they'll pay a little bit more. Someone who makes $1.1 million, a huge amount of money, would pay an extra $4,000. Seventy percent of the money raised by this tax is coming from people who make over $5 million — the richest, wealthiest people in our state, the people who are spending money to oppose this, they know what's at stake. We know that they can afford to pay a little bit more to invest in our schools and our roads and our bridges.

We now turn to Evan Horowitz, executive director of the Center for State Policy Analysis at Tufts University. Evan, you heard the talking points by both sides.

A major point of disagreement is about who and how many people Question 1 will impact. TV ads opposing the question claim that this will primarily affect tens of thousands of people in the middle class — retirees, farmers, small business owners who sell their homes or businesses. Supporters claim that that's not the case at all and accused the "no" campaign of lying about home sales, for example. Which is it?

Evan Horowitz: Well, first, let me say it's great to be here and to be able to do some fact checking with you.

I think on this point, the supporters of the [question] have the right perspective. This is not going to affect tens of thousands of middle-class people. It will affect tens of thousands of people, period, per year — and most of those people will be quite affluent. So the idea that it's a kind of broad middle-class tax, I think, is either farfetched or misguided, depending on how you want to frame it.

Supporters of the new tax say this money would be constitutionally directed to fund infrastructure and education. Opponents argue that there is no guarantee that all of this would be new money for those purposes, as lawmakers could just use it in place of existing funding in the budget. Who's right?

Horowitz: On this one, I think the opponents have the stronger argument. Yes, the Constitution will say, if this passes, that the money has to be used for transit, transportation, public education. But we could take some money that we were otherwise going to put to those areas and move it around and use it for other things.

So ultimately, the money we raise from this tax is not going to increase spending in those areas dollar for dollar with what's raised. Now, just because it's not guaranteed doesn't mean it won't happen. Based on other states' experience with similar kinds of earmarks, we think about half the money will end up in the specified areas, but not all of it.

What will Question 1 actually tax: regular income or capital gains?

Horowitz: It's both. In Massachusetts, we have the same tax rate for capital gains as we have for regular income, so people often don't distinguish. But the millionaires tax would apply also to capital gains.

Are there any other arguments that stand out to you, in terms of inaccuracy?

Horowitz: Well, I mean, just because it applies to capital gains doesn't mean that every time you have a gain, you're going to pay the millionaires tax, right? You still have to have a gain over $1 million. Your total income still has to be over $1 million. So the concern that lots of people who sell their homes are going to end up paying seems overblown. The number of households likely to be struck — be hit by the millionaires tax at the point of home sale is extremely low.

And so even though there's a lot of talk about this kind of one-timers, people who might once in their life pay this 4% surtax from the millionaires tax, they're still not, for the most part, middle-class folks. They're still upper-middle-class folks. They're still relatively wealthy folks whose income rises from $600,000 a year to $1.2 million a year. It's still really a pretty targeted tax on very wealthy people in the state.