As MGM executives celebrated the first anniversary of their casino in Springfield, Massachusetts, this month, they touted visitor numbers, jobs for city residents and the big investment downtown. But it’s been hard to brag about gambling revenue.

Jimmy Diaz moved to Springfield from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. His town was hard hit, and now he lives a short walk from MGM.

"Yeah, I gamble a little bit, trying to get some money," he said. "But instead of getting the money, I’m giving the money away."

Diaz said he visits the casino every other week, and spends about $100 each time at the slots.

"I hardly win," he said with a laugh. "I always lose. It’s not my luck."

So Diaz has contributed hundreds, maybe thousands, of dollars to MGM Springfield’s bottom line. And for casinos, that’s the point: revenue. It’s the same for Massachusetts state officials: a 25% tax on that revenue.

But MGM hasn’t kept up with its own projections.

'A little behind'

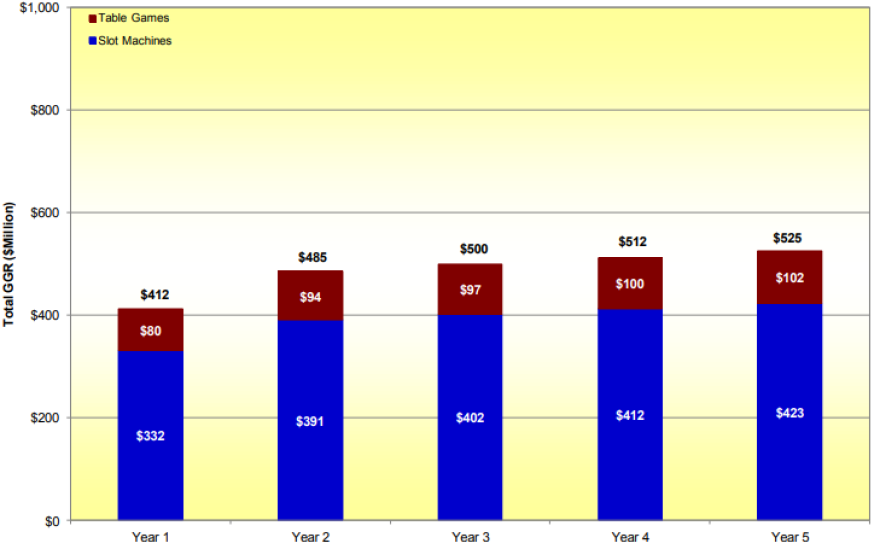

When applying for its casino license, the company told regulators it would generate $412 million in its first year.

Through the end of July — about three weeks less than a full year — MGM reported $253 million in gambling revenue. That fell short of the projection by well over $100 million.

Speaking to reporters last week, MGM Springfield President and COO Mike Mathis defended the estimate as realistic at the time, but he said the regional casino market is tighter now.

"We’re a little bit behind, say, our first-year projections," Mathis said. "But I feel really good about the trajectory of it."

That trajectory is not up. MGM had two of its three worst months in June and July, as competition opened in eastern Massachusetts at Encore Boston Harbor.

Mathis said MGM’s hotel is going strong, as are its restaurants — both of which contribute to different streams of tax revenue. But he acknowledged MGM may not have taken seriously enough the long-established tribal casinos in Connecticut.

"I think we may have underestimated that level of loyalty, and what it would take for those customers to give us a shot," he said.

MGM was not alone in making projections that have proved off-base.

'This size and scope'

About five years ago, Massachusetts gaming commissioners gathered for several days in Springfield, to decide if MGM would get the resort casino license reserved for western Mass. One key area: projected gambling revenue.

Commissioner Enrique Zuniga presented a report from HLT Advisory, a Toronto consultant hired by the commission.

"And that would give us a... total market capture in terms of gross gaming revenues for the facility here in Springfield that would be, in our opinion, between $416 and $485 million a year," Zuniga said.

MGM projected even higher revenue than that after its second year, as it planned to draw more people from outside New England.

That’s an assumption Zuniga and HLT said they found reasonable.

"Because something of this size and scope is likely going to attract people from further away," he said.

And maybe it will — but the total dollars so far are nowhere near the projections.

An outdated model?

That news is utterly unsurprising to analyst Alan Woinski of Gaming USA Corp. (MGM subscribes to his company's publications, Woinski said, but he's never worked for them as a consultant.) Woinski said it’s been a long time since a new casino in the U.S. hit its expected revenue.

"I don’t know if it’s just reluctance to update that model or to bring it up to reality, but it’s been going on for over 10 years now," Woinski said.

One reason the model is not working, he said, is the markets are just too crowded. MGM competes with Connecticut casinos, one in Schenectady, New York, Twin River in Rhode Island — and the other two in Massachusetts.

But Woinski will not blame the industry for using unrealistic numbers. He blames elected officials who welcome gaming laws tied to outsized hopes. That pressure gets channeled from regulators to casino companies to the analysts making the projections.

"When you pass a gaming law, whether it’s a new gaming law or whether it’s an expansion, you need to be realistic," he said.

The state’s first casino, the Plainridge Park slots parlor, came in well under projections when it opened in 2015, and those numbers haven’t moved much.

At this point, the state’s gaming commissioners are not publicly complaining about the disconnect between projections and revenues. Their message through the years: some casino tax revenue is better than none.

In a statement, chairwoman Cathy Judd-Stein said the commission is monitoring revenue trends, but said “gaming as an economic development tool is a long-term play.”

Nancy Cohen and Adam Frenier contributed to this report.