Sign up for the CommonHealth newsletter to receive a weekly digest of WBUR’s best health, medicine and science coverage.

Blood work was supposed to be the last step in Isela’s application for life insurance. But when she arrived at the lab, her appointment had been cancelled.

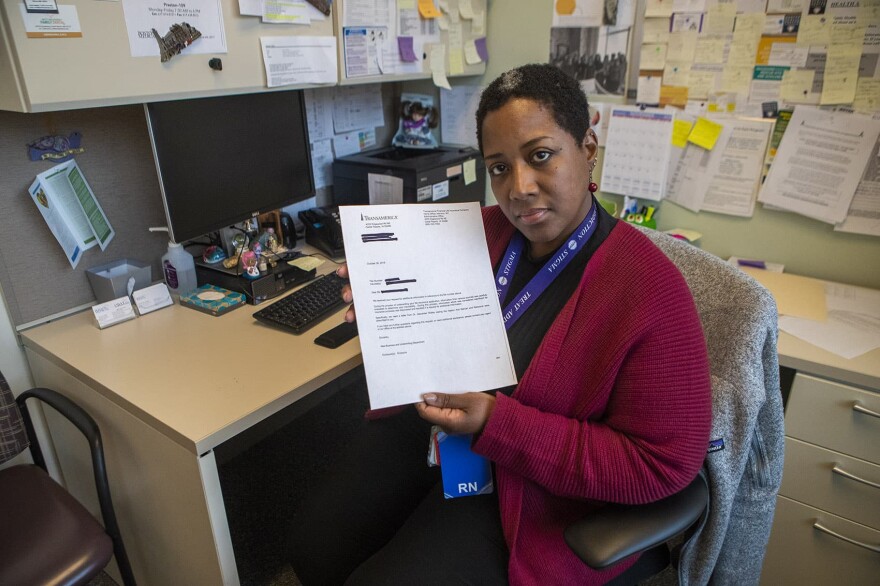

“That was my first warning,” Isela said. She contacted her insurance agent and was told her application was denied because something on her medication list indicated that Isela uses drugs. Isela, who works in an addiction treatment program at Boston Medical Center (BMC), scanned her med list. It showed a prescription for the opioid-reversal drug naloxone, brand name Narcan.

“But I’m a nurse, I use it to help people,” Isela remembered telling her agent. “If there is an overdose, I could save their life.”

That’s a message public health leaders aim to spread far and wide. “BE PREPARED. GET NALOXONE. SAVE A LIFE,” summarized an advisory from the U.S. surgeon general in April.

But life insurers consider the use of prescription drugs when reviewing policy applicants. And it can be difficult to tell the difference between someone who carries naloxone to save others and someone who carries naloxone because they are at risk for an overdose.

Primerica is the insurer Isela says turned her down. The company says it can’t discuss individual cases. But in a prepared statement, Primerica noted that naloxone has become increasingly available over the counter.

“Now, if a life insurance applicant has a prescription for naloxone, we request more information about its intended use as part of our underwriting process,” said Keith Hancock, the vice president for corporate communications. “Primerica is supportive of efforts to help turn the tide on the national opioid epidemic.”

Isela applied to a second life insurer and was again denied coverage. But the second company said it might reconsider if she obtained a letter from her doctor explaining why she needs naloxone. Isela contacted her primary care physician but soon realized: Her doctor did not prescribe the drug.

Isela had bought naloxone over the counter at a pharmacy, as can anyone in Massachusetts. To help reduce overdose deaths, the state has established a standing order for naloxone — one prescription that works for everybody. Isela couldn’t just give her insurer that statewide prescription; she had to find the doctor who signed it. Turns out he also works at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Alex Walley works in addiction medicine at BMC and is the medical director for the Opioid Overdose Prevention Pilot Program at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

“We want naloxone to be available to a wide group of people, people who have an opioid use disorder themselves but also [those in] their social networks and other people in a position to rescue them,” Walley said.

So Walley is troubled by the handful of denied life and disability insurance applicants who’ve asked him to write letters, explaining why they need the drug.

“My biggest concern is that people will be discouraged by this from going to get a naloxone rescue kit at the pharmacy,” Walley said. “So this has been frustrating.”

The life insurance hassle has discouraged Isela and some of her fellow nurses. (We’ve agreed just to use her first name because Isela is worried about how this story might affect her ability to get life insurance.) She is not carrying a naloxone kit outside the hospital right now because she doesn’t want it to show up on her active medication list until the life insurance problem is sorted out.

“So if something were to happen on the street, I don’t have one, just because I didn’t want another conflict,” Isela said.

BMC has alerted the state Division of Insurance, which said in a statement it is reviewing the cases and drafting guidelines for “the reasonable use of drug history information in determining whether to issue a life insurance policy.”

But Isela isn’t a drug user and yet she is still being penalized as if she is. Michael Botticelli, who runs the Grayken Center for Addiction Medicine at BMC, says friends and family members of patients with an addiction must be able to carry naloxone without fear that doing so will send them to the insurance reject pile.

“It’s incumbent on all of us to make sure that we try to kind of nip this in the bud before it is any more widescale than what we think might be happening,” he said.

Botticelli says more widespread access to naloxone is one of the main reasons overdose deaths are down in Massachusetts. The most recent state report shows 20 fewer fatalities this year as compared to last.

Botticelli relayed his concerns in a letter to U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams, who said he contacted the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and was told there is “no indication this is a widespread issue.”

Adams said his campaign to expand the use of naloxone continues.

“The science tells us that naloxone saves lives, and it is important that all Americans know about the vital role bystanders can play in preventing opioid overdose deaths when equipped with this life-saving medication,” said Adams.

Copyright 2018 WBUR