"Afrocosmologies: American Reflections," at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, is an exhibit of more than 100 paintings and sculptures that weave a historic, generational story of black American art.

Some well-known artists like Martin Puryear and Kara Walker are in "Afrocosmologies," along with many lesser-knowns.

Exhibit curator Frank Mitchell, director of the Amistad Center for Art and Culture, said what's interesting is how some artists represent themselves.

"Many of the artists are highlighting where their parents, or where they, originate within the diaspora," Mitchell said. "So some think of themselves as Haitian American, and some think of themselves as clearly from some part of West Africa."

There is an inherent tension in an exhibit that features a collection of black artists with different experiences from different eras.

Mitchell wrestled with the best way to put material from established masters next to their contemporaries, he said. The convergence was around spirituality and religion.

“We started creating this cosmology, or sort of a cosmos — a way of ordering all that chaos," he said. "It all tilted towards Africana and Africana studies — so, 'Afrocosmologies.'"

On a late fall evening, several artists from the show were at the Wadsworth Atheneum to speak about how spirituality takes visual form in their work.

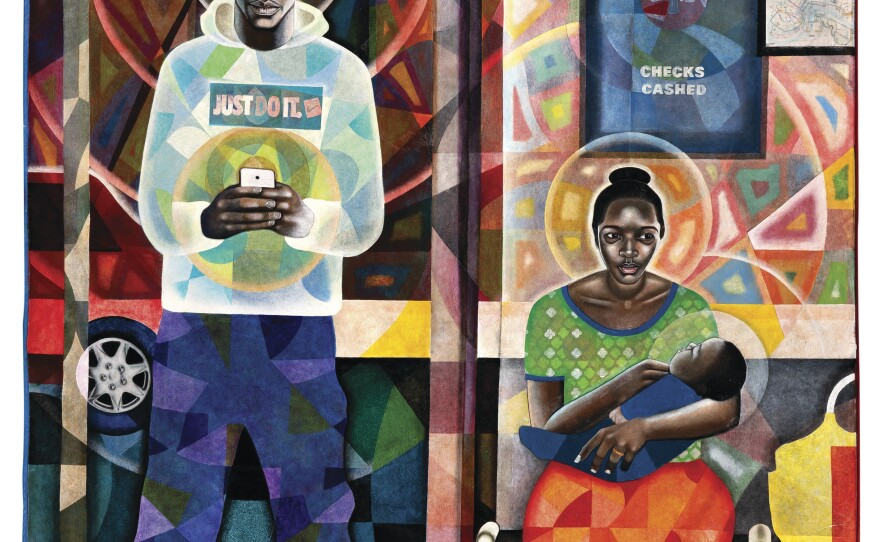

Carl Joe Williams came in from New Orleans. His piece “Waiting" is hung on the third floor. The canvas is a discarded twin mattress. Williams paints his subjects in a cubist style.

"A lot of my work has to do with the breakup of the black family, and just families in general," Williams said.

In "Waiting," Williams created a scene of a man, a woman and a baby, "together at a bus stop, but separated," he said. "Separated by the bus stop itself, and in life."

The woman is holding the baby, sitting inside the frame of the bus stop, looking outward. The man, with a "Just Do It" sweatshirt, is standing, staring at his cellphone. They appear to have halo glows around their heads, like in Italian Renaissance paintings. Behind them are advertisements in a store window for soda and check cashing.

This is a slice of American culture, Williams said.

"I'm interested in all these kinds of things that affect our lives on a daily basis, and it's important for me to tell the story of disenfranchised people," he said. "I feel like I'm from that, so it's imperative to me to represent that in my work."

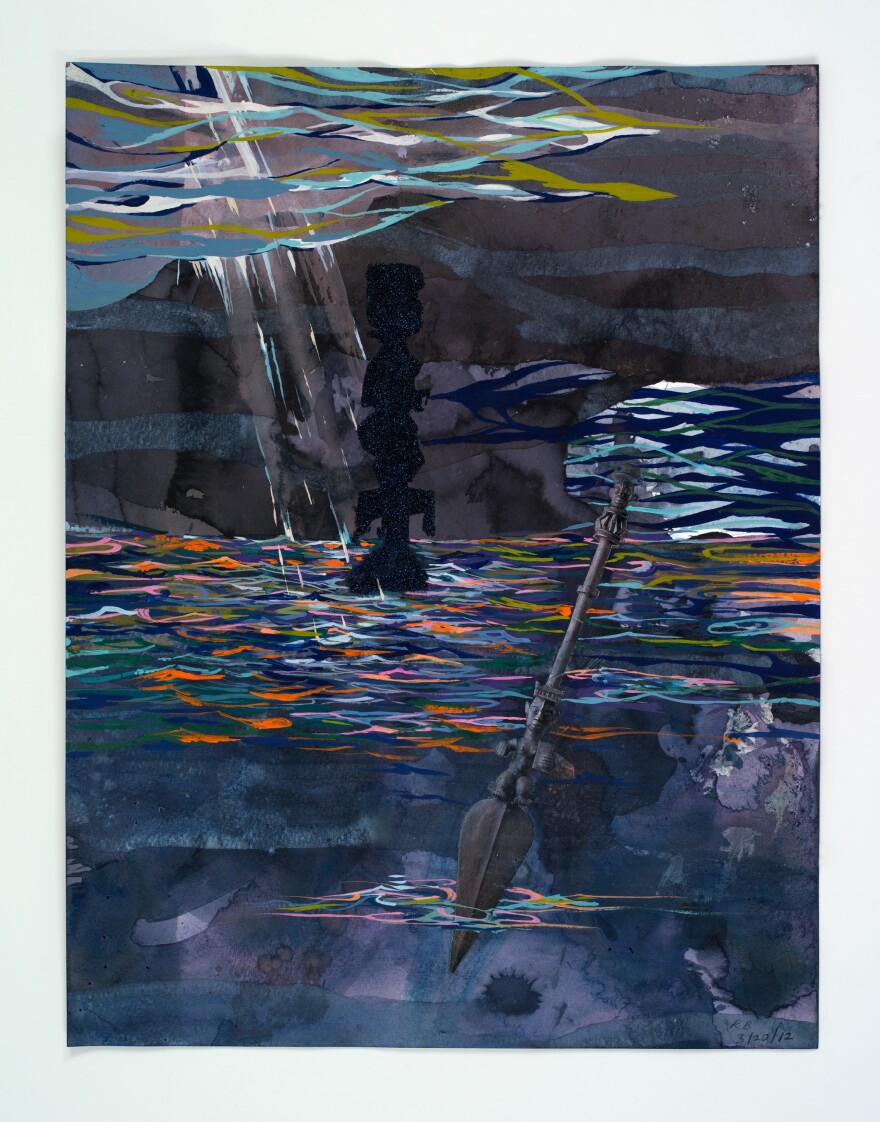

On the second floor is "Storm," a painting by Radcliffe Bailey from Atlanta. The piece, he said, is part of a series he began in Europe.

"I started working on this work right after a visit to the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, after seeing the collection of art from the Congo — and other African art taken by [King ] Leopold [II]," Bailey said.

Bailey remembers going into storage areas where some art hadn’t seen the light of day in years.

"Storm" is a small painting of furious-looking waters. It's about Africans lost at sea, Bailey said, and about how African art has traveled around the world, and affected and influenced people.

"You have to think about the struggle, the time period," he said. "Being creative as an African American artist, making art in the 1940s or or the 1800s or the early 1900s, and to see their work today — it's a beautiful thing."

Artist Berrisford Boothe, who also has a piece in the exhibit, moved to Hartford from Jamaica with his family when he was 10 years old. As a young black child, he said he remembers standing across the street from the Wadsworth, terrified.

"I thought I was never going to go in there. It’s just rich white people who will never let me in," Boothe said.

Boothe's story of a relationship with a museum is not just anecdotal, he said. It’s a message for all young people of color who are afraid to move in these kinds of environments.

"They have to," he said. "They have to inhabit the spaces and the world as [they] see it, and from there art is born."

Boothe is now the art department chair at Lehigh University, and the principal curator for the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African-American Art. The foundation collaborated with the Amistad Center and the Wadsworth on "Afrocosmologies," which closes January 20.