This weekend in Florence, Massachusetts, a premier concert performance will feature music composed by jazz saxophonist Tiyo Attallah Salah-El.

Salah-El was also an author, scholar and activist who died in a Pennsylvania prison in June 2018, at age 85. He’d served nearly 50 years of a life sentence for a murder he always insisted he did not commit.

The concert at the Bombyx Center will celebrate a new recording many years in the making, called “Tiyo's Songs of Life,” arranged by saxophonist and UMass music professor Felipe Salles and produced by Lois Ahrens, founding director of The Real Cost of Prisons Project.

The band includes pianist Zaccai Curtis, bassist Avery Sharpe and drummer Jonathan Barber.

On the titles of the songs, such as "Toe Tappin' Tasty”:

Felipe Salles: I love the titles. The titles are so, so — Tiyo. Like, from what I have gathered from his writings, he had a very interesting way of talking and...

Lois Ahrens: Kind of a groovy guy.

Salles: Very groovy.

Ahrens: He was. He really was.

Salles: And a lot of the music, I think, it has a groove and a dance and a perky quality to it, you know, that I think is very clear in the music.

On when Ahrens first corresponded with Salah-El, in 2005:

Ahrens: I started this project of creating these comic books about prisons and the war on drugs and women in prisons. And my idea was to send them to prisoners and organizers around the country. And [Tiyo] saw the little announcement, and he wrote me and I sent him three comic books. And he wrote me back immediately, and that's how we met.

And for all of those years that I knew him, we probably communicated at least one time a week through the mail. I think I went to see him in 2008. He had not had a visitor in, maybe, 20 years.

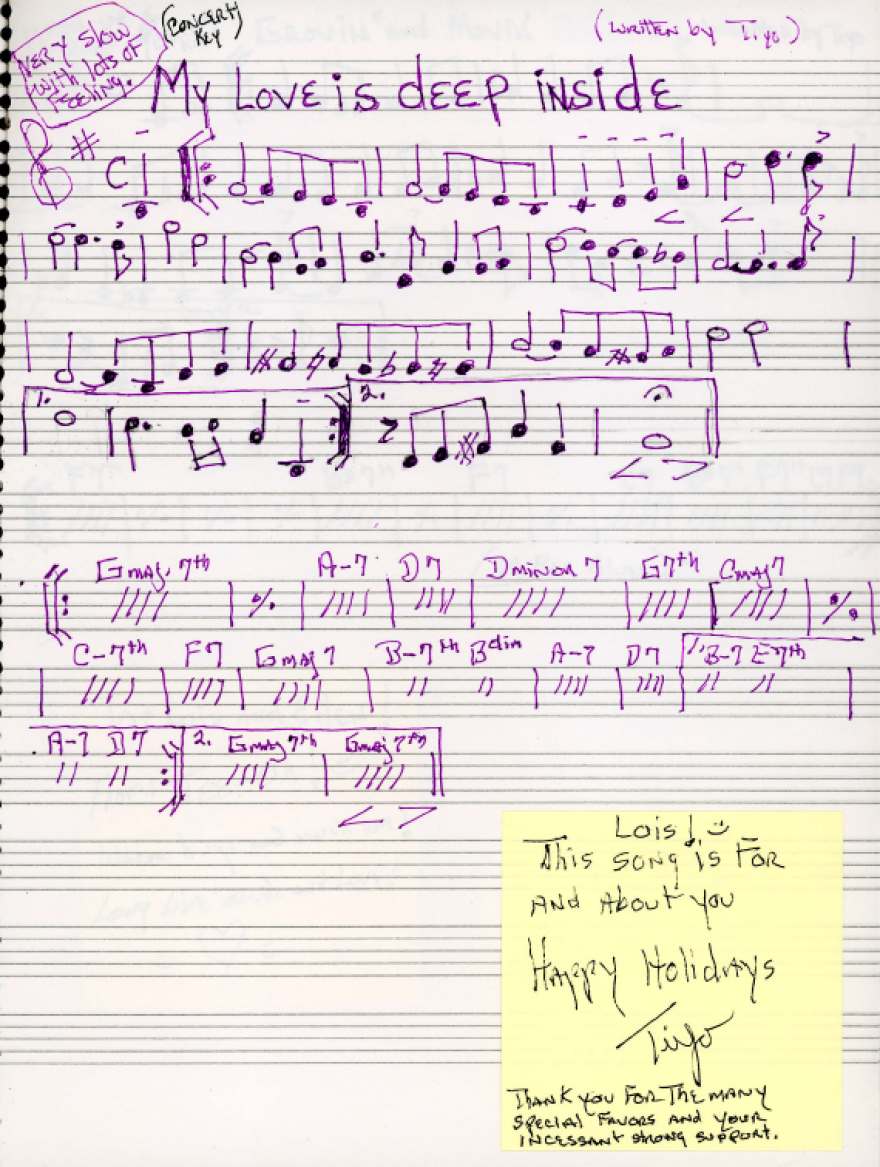

On what happened after Ahrens sent Salah-El some blank music paper, at his request:

Ahrens: A few months later, I got all these songs back. I thought, 'Well, I don't read music. I have no idea what these even sound like.' So I approached one person who I knew or I'd heard about — there was a sax player. He couldn't do it for some reason. And then he said, 'Oh, call this guy.' And I called that guy and blah, blah, blah. Anyway, this went on for many, many years.

On Salles agreeing to work on the music, after he completed a multimedia project on the immigrant experience:

Salles: And then I finally sat down and was like, 'OK, let me look at this music. But then, I think, Tiyo's book was coming out, right?' And I was like, 'Look, I don't want to just look at this music with no reference. You know, this doesn't seem right to me?’

So [Ahrens] was patient enough that I bought the book and I read the book. And so I thought about it, and then went back to the music and said, 'OK, now I understand a lot more about this guy's life, his personality, what this music is coming from. Now I can start writing some arrangements.'

And then I start talking to some musicians who I thought would be the right people to do the recording based on the style of the music, and also the whole social engagement and activism that was related to that. I wanted to make sure that I was doing the right thing, you know, honoring the music and the project the right way.

On how Ahrens felt when she first heard the music:

Ahrens: Oh, I mean, I was — just even talking about it — Felipe sent it to me, like, on my birthday. Just by chance. It's beautiful song.

Salles: I think that was the first one I arranged. I took my phone and I played that on the piano, and I think I sent it to you, and you were like, 'Oh, what is this?' I was like, 'That's the song that he wrote for you.' And you couldn't believe it. You were like, 'Oh, my God, I can't believe this is, you know, how it sounds like.' It is one of my favorite tunes in the record.

Ahrens: I know. Just after all of these years, I mean, since getting the first music, it's been 17 years. And to have so many false starts and to actually hear how beautiful it was — it was very moving.

On whether Salah-El ever got to hear the music:

Ahrens: No.

Salles: He had a band in prison for a while, right?

Ahrens: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, he was in prison for so long that the kinds of conditions in prisons changed during the time of his incarceration. So like in the early seventies, there were a total of 200,000 people in the whole United States incarcerated. And by the time he died, there were 2.2 million people in prison.

So he lived through this whole era of the building up of mass incarceration. And when he was first in prison during those first years, because there were so few people comparatively in prison, prisoners had a lot more access to doing things. So people could learn and take classes and get degrees and have bands — and people from the outside could come and hear them play. And, you know, it was just a very different carceral world than the world that we're living in now.