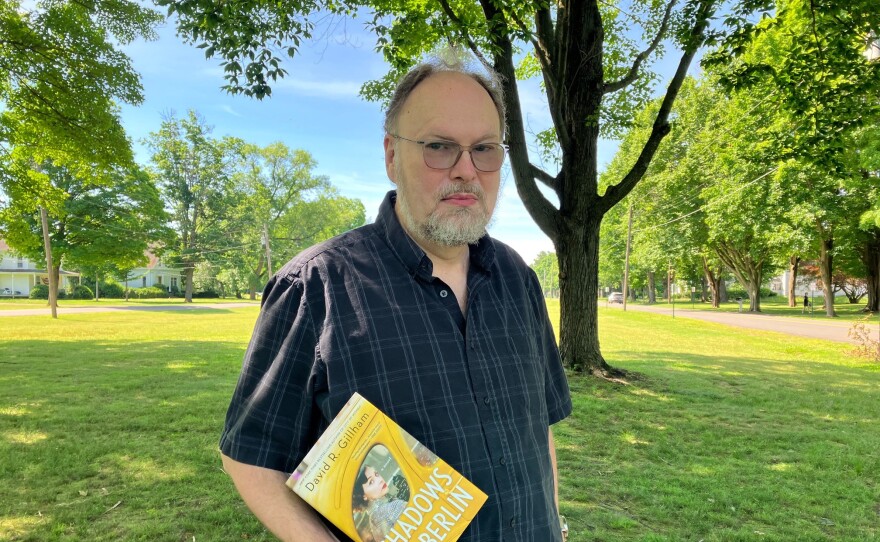

In his new novel, "Shadows of Berlin," author David Gillham, of Amherst, Massachusetts, explores the themes of grief, guilt, redemption and hope. The main character is Rachel, a German Jewish Holocaust survivor living in New York a decade after World War II ended.

As Gillham explains, Rachel married an American Jewish man who spent the war stateside — and he is somewhat oblivious to the horrors his wife and others endured.

David Gillham, author: They both see an opportunity to sort of save themselves in a way, or hope to. And this is 1955. You know, it's instant coffee, it's color TVs. It's limitless futures. And she thinks she can sort of escape herself there in this marriage. And, Aaron, her husband thinks, "OK, I can marry this poor refugee woman and save her, redeem her. And that way I can get rid of my own guilt." Now, these aren't concepts that they're necessarily thinking, but this is what drives the character.

Nancy Eve Cohen, NEPM: Can you help us understand this character, Rachel? How did you come to her?

I started out thinking about (how) I wanted an artist. Somebody who has some avenue of expression that she can pour herself into. And then she evolved as I wrote scenes with her husband. There's a lot of banter and bicker between them, and that really helped me define both of them really well, I thought.

And then she sees a "shrink," as she calls it, and that gives me the opportunity to literally explore on the page her inner self without having to narrate it. I can do it through dialogue. I sort of built the character as I build the story, which is scene to scene, almost moment to moment sometimes. That's how Rachel evolved.

Is there one part of the book that would help us understand Rachel a little bit?

So, this particular excerpt, Rachel is in New York. She's at her kitchen table in their apartment in Chelsea. And she's doing a self-portrait of herself, which is what she does over and over again. But it's in the distorted reflection of a toaster. And her mother appears. She's haunted by her mother, who had perished in the Holocaust, throughout the book, in one way or another. And so her mother says:

So we are here, you and I, she hears her mother observe. Azoy, mir zenen do. Always, between them, it's Yiddish.

"Yes, Eema. We are here."

Peering at her daughter with her usual mix of curiosity and disapproval, she wonders, What is this you are doing?

"I'm drawing," Rachel tells her.

Really? Eema is skeptical. Is that what you think? This qualifies as drawing?

"Es iz a shmittshik," Rachel says and then pick out a few words from English. "A doodad, you know? A doodle."

So you may call it. But is it a waste of your God-given talent?

"And now it's about what God gives us, Eema? I thought my talent came from you. Besides, you said you had abandoned God."

Eema replies in a leaden tone, Of course! This is how a daughter speaks to her mother. Let's be correct, Rashka. I did not abandon God. God abandoned me.

It seems to me one of the hardest things that the main character is dealing with, that Rachel is dealing with, is struggling with the trauma of having survived at the expense of others.

Yes.

Can you talk a little bit about what she had to do to survive and why you chose that storyline?

This was actual history that there were Jews who had been arrested by the Gestapo in Berlin who were basically turned into "catchers" — that's what they were called on the streets, who would go out and hunt other Jews for the Gestapo. And they were privileged, you know, they were given money and rewards. Even though they were still locked up in this transit camp on the Grosse Hamburger Strasse, they were given power.

There was one woman in particular who was known as the "Blonde Poison" who was infamous on the streets. She had tricks about waiting outside of embassies to try to catch Jewish people who were coming out, who had failed to get a visa. And so, I based one of the characters in my book on her. And she decides to start grooming Rachel as a "catcher."

Why did you want to write about this incredibly horrific experience that some people had, that this character had — guaranteeing her own survival by helping the Nazis catch other Jews?

I really wanted to put that character in one of the worst situations that she could possibly encounter in order to then try to save her. I wanted to amplify the disasters that fall to her soul in order to then try to fix her in some way, to redeem her in some way or help her redeem herself.

I mean, I sometimes get so involved in the characters that I do think of them as, you know, doing something on their own. And so, that's why I picked it.