This month marks 20 years since General Electric Co. signed an agreement to clean up PCBs the company had dumped in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

Back then, the community was not only grappling with widespread contamination, but also the aftermath of losing thousands of GE jobs in the city.

As a sign of GE’s continued struggles, just this week it announced some 20,000 salaried employees will stop accruing pension benefits. That doesn’t affect current retirees.

For decades, multiple generations in many Pittsfield families worked at GE. The company provided workers — even those without experience — a way up.

Just ask Dave Gibbs, who grew up half a block from the plant.

“My mother [worked there], my grandfather did, my grandmother did, my aunt,” Gibbs said — and he also had a job at GE for a short time.

Workers got good pay and benefits. They could buy a house, a car, and even get a pension — the kind of job that’s almost unheard of today.

“It was part of everybody’s life,” Gibbs said. “It was ‘The GE.’ That’s what everybody called it. ‘The GE.’”

“The GE” played a major role in the community. It had a social club and an appliance store with discounts for workers, and it was a key contributor to charitable organizations.

The GE factory was like a city unto itself, with its own credit union, medical centers and fire department, encompassing about 250 acres.

Al Bertelli also worked at GE. Now 80 years old, he grew up near a footbridge over the east branch of the Housatonic River, just down the hill from the plant. His father, Angelo Bertelli, “commuted” to GE over this little bridge.

“I remember Dad walking with a couple of guys from the neighborhood,” Bertelli said. “Most of the time, Dad worked the second shift. So I [would] see him going to work sometimes. But coming home, he’d be coming home in the middle of the night.”

"My Dad loved two things. He was an immigrant. He loved this country and he loved the GE, sometimes, I think, more than us kids."

Al Bertelli

Angelo Bertelli started at GE in 1916 and worked there for 41 years operating a crane. He was known as “Ange the Crane Man.”

“My Dad loved two things,” Al Bertelli said. “He was an immigrant. He loved this country and he loved the GE, sometimes, I think, more than us kids.”

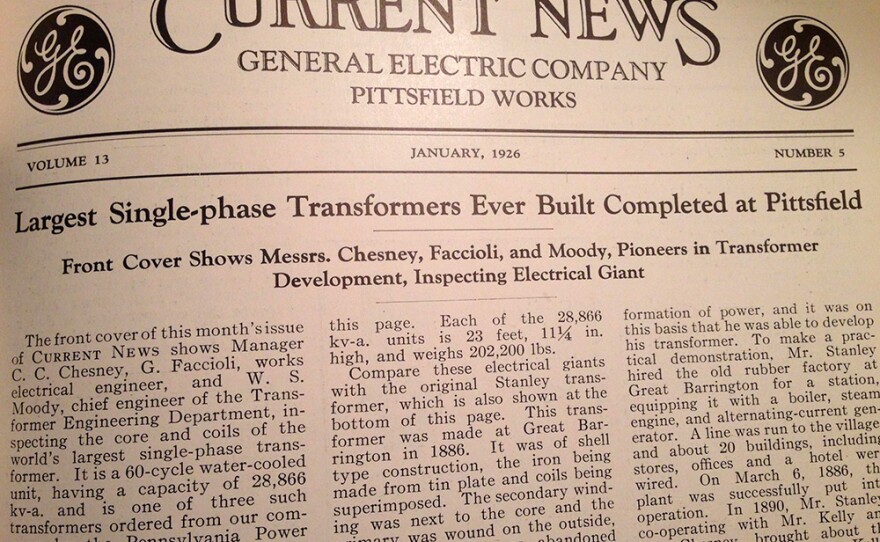

GE first opened its doors in Pittsfield after buying The Stanley Electric Manufacturing Company in 1903 — known as The Stanley Works.

William Stanley was an early innovator of power transformers. That technology can shift the voltage of electrical current to high voltage and back down again so it can be distributed safely over long distances.

Starting with its transformer operation, GE grew into an economic force that dominated Pittsfield.

By 1943, nearly 14,000 people worked there.

About once a month, dozens of GE pensioners still gather for a meal at the Berkshire Hills Country Club in Pittsfield. One day last fall, roast pork was on the menu. GE is still offsetting the cost of these lunches.

Peter Nykorchuk was there. While it wasn’t unusual for people to get a job at GE straight out of high school, he started even earlier, at age 16.

“I was a co-op student. I took machine shop,” Nykorchuk said. “I was working in Building 42 to the apprentice department. Then, when I graduated, I got into the apprentice program, graduated apprentice and I made it all the way up to Class A toolmaker. That was 37 years.”

Dick Taikowski started in 1958 as a tinsmith’s helper in maintenance.

“Building different blow pipes, exhaust systems, flashing, roof flashing. As a tinsmith we did everything.” Taikowski said. “I have no regrets of working for General Electric for 40 years.”

Richard Floyd arrived in the city in 1982. Now he’s the pastor emeritus at the First Church of Christ. His congregants included GE managers and workers.

“Every second person you met worked for GE,” he said.

Floyd said employees had money to spend in the local economy, along with lots of retirees, “who got good GE pensions,” he said. “And they were part of the economic infrastructure of the community too, because they could afford haircuts and restaurant meals and the like.”

Floyd has a vivid memory of a bustling downtown in the early 1980s.

“You’d see your neighbors shopping, and it was a community thing,” he said. “It was very binding of the community.”

Charles Cleveland, a retired welder, remembers the traffic near the GE plant on East Street.

“There were lines of cars on both sides of the road. Everybody working in GE,” he said.

Cleveland started in 1967, first repairing and then building the sometimes big steel tanks that housed the power transformers.

“If I stood up, it would be probably up to my head,” Cleveland said, holding his hand up high. “Yeah, they were good-sized. And there was bigger ones than that.”

Sitting opposite him at their dining room table, Cleveland’s wife, Shirley Cleveland, said she was learning something new.

“I lived with this man for 56 years. I’ve never heard about his work,” Shirley Cleveland said with a laugh. “All I knew was he came home with a paycheck. It’s interesting.”

The transformers were placed in the tanks, which were filled with oil containing PCBs, a chemical compound that isn’t flammable. When electricity moved through the transformer, the PCB oil acted as an insulator and prevented the transformer from “arcing,” or sparking.

Employees, at times, breathed in PCB fumes, or got the PCB oil on their clothes or skin.

“You know, you get your elbows in it, and it’s on your shirt. I bring them home, and [Shirley would] wash them,” Charles Cleveland said.

“Sometimes when he walked in the door, you could smell it,” Shirley Cleveland said. “But it would be on his clothing. So I was touching it. I was throwing it in the wash.”

The EPA now says PCBs can cause a “multitude of serious adverse health effects” in the reproductive, endocrine, immune and nervous systems. The federal agency classifies PCBs as a probable human carcinogen.

By 1979, Congress had banned them.

In 1998, Shirley Cleveland was diagnosed with bladder cancer.

“We’re thinking it might have been from that,” Charles Cleveland said about the PCBs. “But you know, you can’t prove it. You know, you couldn’t ask a doctor, especially in Pittsfield. They’d say, ‘No,’ you know.”

Shirley Cleveland also wonders if the PCBs had made her sick. Despite the cancer, which is gone now, she had good things to say about GE.

“For us there was security,” she said. “The pay was good. You had good insurance. You didn’t have to worry about losing your job, like they do today.”

But it wasn’t all good between workers and the company. There were strikes or walkouts as early as 1916 and into the 1980s.

Still, there was a lot of pride in the work.

Al Bertelli was an assembler in the power transformer division. He started at GE in 1962.

“They put a power transformer through five times the test in Pittsfield before they shipped it,” he said. “They were the best. They were the best in the world.”

But Bertelli also said the PCB oil was “nasty stuff” that kind of numbed his skin.

“Sometimes you had to assemble a transformer and get your arms right into the oil,” he said. “Any cut or hangnail or scratch that you had, and that stuff would burn. And you go to the dispensary and get this black, brown salve, and rub it all over your arms, and get the feeling back.”

Later, Bertelli got cancer, but he isn’t sure if the cause was PCBs, smoking or something else.

Bertelli remembers seeing PCB oil being dumped at the plant.

“There was a spill. I could see a manhole cover open,” he said. “They were squeegeeing the liquid down to the manhole. Manholes ran to the river.”

Other workers have also reported the oil being dumped into storm drains that led to the river, or dumped right onto the ground.

Bertelli is now the vice president of the environmental group Housatonic River Initiative.

GE and the EPA have cleaned up the first two miles of the Housatonic River south of the plant. As they begin cleaning up the rest of the river, they’re at odds about where to dispose of the PCBs.

The city not only grappled with PCB contamination, but also job loss. In 1986, GE announced it was shutting down most of the power transformer division. According to The Berkshire Eagle, within five years, the number of GE jobs in Pittsfield were cut nearly in half, down to 3,600 employees.

And the GE jobs kept leaving.

“We were the last maintenance crew to close down the plant before demolition,” said David Zatorski, who was an employee for about 39 years. “Our group cut off the power and the steam to all the buildings, and we got out all the PCB transformers that were in there... That was our job the last three or four years I was there.”

By 2007, the company sold its last division in the city. Today, only a small staff remains in Pittsfield.

Sitting in his kitchen in Pittsfield, Bertelli said he is full of a mix of emotions when it comes to GE.

“It ain’t right, what they did to this area,” he said. “They devastated it. They polluted it.”

Bertelli said GE took away good jobs. And yet…

“Look at the emblem on the refrigerator,” he said. “I [am] still dedicated to that little GE emblem.”

Almost every appliance in Bertelli’s kitchen is made by “The GE.”

Check out “Pittsfield After GE: Mosaic Of Businesses, But Short On Trained Workers,” the second of a two-part series on GE’s local influence.