The pandemic has affected every person’s life, but there is consensus that communities of color — especially Black and Hispanic — have been affected the most.

However, in Massachusetts, the data to prove that is hard to pin down.

If you look at the state of Massachusetts’ COVID-19 dashboard, and click on the race-and-ethnicity tab, you could get the impression people of color have died in lower numbers than expected, given the population.

By April 2021, Black residents made up 6.5% of deaths in the state, which is a bit lower than the percentage of Black people in the population. Hispanic residents made up 8.5% of deaths, compared to 12% of the population.

But research analyst Abby Raisz of the UMass Donahue Institute said these numbers don’t tell the whole story.

“That's because white people are older. They’re just a much older demographic than the Hispanic or Latino population, which is very, very young,” Raisz said. “So it's ... a not super accurate way of looking at deaths."

Older people are more likely to die of COVID, whatever their race. So to better compare different groups, Raisz and her colleagues crunched the numbers again and adjusted for age.

“And from there, we were able to see just a skyrocket in rates for the Black and Hispanic or Latino populations who died of COVID19,” she said. “The white rate actually decreased when you adjust for age.”

In a report for Boston Indicators, researchers found that Black and Hispanic residents died at more than three times the rate of white people, using August 2020 numbers.

Since that difference could no longer be explained by age, Raisz said, “what that instead indicates is that they're dying because they have other comorbidities or their conditions are just really crappy, be it housing, where they're working.”

Those numbers are averaged across the state. Raisz said she does not know whether disparities are worse in some regions compared to others because the state doesn’t break down numbers that way.

The state health department declined comment for this story.

“I feel frustrated,” Raisz said. “We were hoping that by this point we would be getting death data by city and town (and) by race.”

'The level of blanks ... is still really problematic and unsettling'

Apart from deaths, racial disparities in cases of COVID are even harder to pin down because not every provider keeps track of that information, and reporting varies among agencies.

“The level of blanks that we get in the data is still really problematic and unsettling," said state Senator Sonia Chang-Diaz, who has been vocal about disparities during COVID. "There's just sort of a statistically disruptive number of unknowns."

Some individual cities, however, do report deaths by race – such as Springfield. But Springfield’s numbers don’t show many disparities in the approximately 240 COVID deaths so far.

According to a recent city count, 41% of deaths in Springfield were white people — which is actually higher than their share of the population. Black and Hispanic deaths account for about 22% and 34%, respectively, of all deaths in Springfield — similar or less than their share of the population. However, those numbers would likely change if age were accounted for.

The city's health and human services commissioner, Helen Caulton-Harris, said she hadn’t considered that.

“I mean, that could potentially be,” she said. “I would have to go back ... and look at the race and the age.”

Caulton-Harris said Springfield has hired an outside agency to pore over the numbers further.

Many other western Massachusetts cities don’t post the data by race at all, even though the death certificates include that information. A clerk for the Holyoke health department said the office does not track deaths by race. The health director did not return messages, nor did health directors for the other three largest cities in western Massachusetts — Chicopee, Westfield and Pittsfield.

'The ripples are really what is devastating'

Caulton-Harris cautioned, however, that focusing too much on numbers — be it COVID infections or deaths — misses some key ways disparities show up.

“We are talking about also the social determinants of health [such as] housing, food insecurity, jobs, living wages,” she said. “The raw numbers give us some guidance as far as the impact is concerned. But that, for me, is like putting a pebble in the middle of a pond. The ripples are really what is devastating.”

Tanisha Arena, director of the Springfield organization Arise for Social Justice, hasn’t been following the data either; she’s been watching COVID up close. She said three of her seven staff members have gotten the virus and they were all people of color.

But Arena said racial and economic disparities are hardly new, starting with the types of jobs people have.

“The gas station attendant, the person that works at Walmart, the one in the grocery store, folks in the hospital — not just the nurses and the doctors, but housekeeping,” Arena said. “The rates of exposure are higher in those spaces. And, it's like, who does that work?”

'The ugly truth'

Arena said people of color in Springfield are also more likely to be homeless or live in crowded housing, which are risk factors for getting COVID. They also have higher rates of asthma.

“It showed the ugly truth,” she said. “I think the pandemic is showing the depth and breadth of disparity and the amount of work that has to be done.”

Community leaders and analysts are now watching to see whether the vaccine rollout does a better job at reaching communities of color.

Raisz, of the Donahue Institute, said the state does a much better job of tracking vaccination data by race.

“You can get down to the zip code or the city and town level. You can get the race, you can get age. It's really good data,” she said. “It's what we were wanting this whole time for for cases and for deaths.”

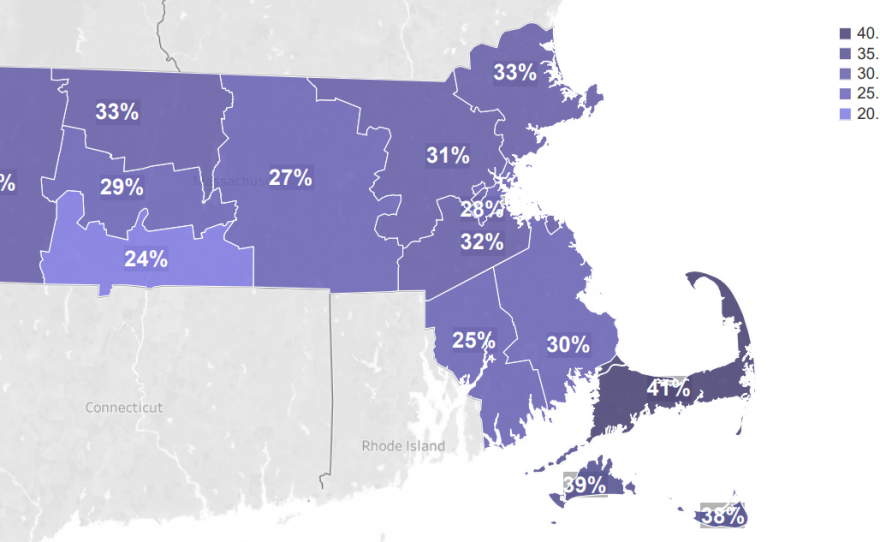

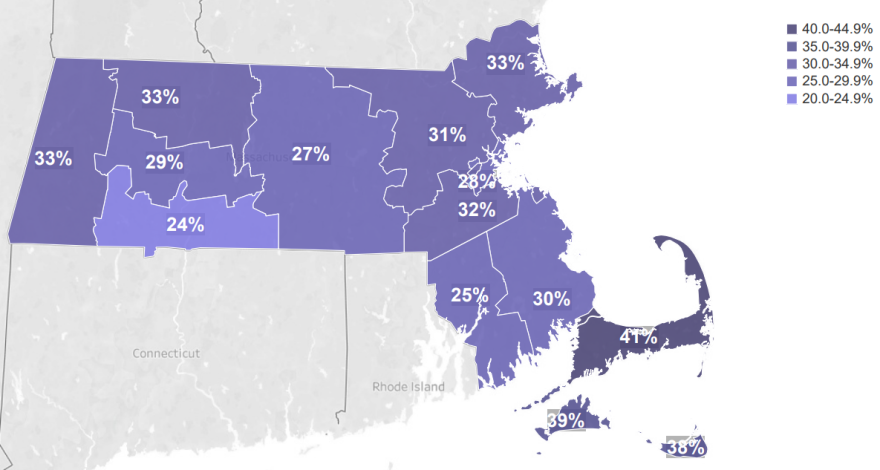

Raisz hasn’t crunched the vaccine data, but a recent state update does show significant racial disparity in western Massachusetts, particularly for Hispanic residents.

And Hampden County — the most populated and racially diverse county in western Mass. — continues to trail the rest of the state in the percentage of people who are fully vaccinated.

Missed opportunities

Looking at the data across Massachusetts, a recent state update showed Black and white residents who had received at least one dose mostly matched their percentage of the population, but there was a large gap among Hispanic residents.

Chang-Diaz, who is considering a run for governor, said better data collection by the state might have reduced disparities in vaccination rates. She’s frustrated the state doesn’t list COVID cases or deaths based on occupation, as the legislature had demanded. She said frontline workers like grocery or food service are more likely to contract COVID — and those occupations have higher rates of Black and Hispanic workers.

Those workers were fairly low on the state’s vaccine priority list — the end of phase 2, after people 65 and up, educators and people with two underlying conditions.

“We've got a huge proportion of communities of color working in those industries,” she said. “Where the pandemic has hit the hardest, that's where we should be focusing the most for vaccination. I think it's a really simple, intuitive metric for people, but the administration has not committed to that. And they have not answered questions about how they’re measuring success.”

Meanwhile, some institutions are choosing to take action on the assumption disparities exist, even without clear-cut data.

Dr. Paul Perraglia oversees community outreach for Baystate Medical Center, Springfield’s biggest hospital. He said his team didn’t know the racial breakdown of COVID patients or deaths at the hospital but they knew Black and Hispanic patients make up the majority of Medicaid patients in their system.

So the hospital distributed materials in those communities they thought would be helpful in keeping the virus at bay. Those ranged from hand sanitizer and cleaning supplies to inflatable mattresses and room dividers so that people in crowded homes could isolate if necessary. He doesn’t know if that prevented infections or deaths.

“Proving effect or proving that there was actually a difference,” Perraglia said, “is very, very difficult to do.”